I’m researching Berlin in the 1980’s for an upcoming writing project. Many people who grew up after the collapse of the USSR (like myself) are only vaguely aware of the historical context surrounding the Berlin Wall.

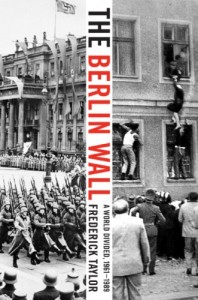

So, I’ve put together this blog post with some interesting facts I came across while reading Frederick Taylor’s book The Berlin Wall: A World Divided 1961-1989.

1) What was the Berlin Wall?

First of all, calling it a wall is a bit misleading. Most of the Western photos I was familiar with show a graffiti slathered ten foot concrete barrier dotted with guard towers and barbed wire.

But by the time it was torn down in 1989, the “wall” consisted of a barrier fence, a carefully raked warning track to show trespasser footsteps, tank traps, self-firing guns, searchlights, and attack dogs, followed by the ten foot barrier people stared at from the West. It was a feat of East German engineering, intentionally designed to kill anyone who tried to cross it.

2) Where was the Berlin Wall?

As an elementary student I imagined the Berlin Wall bifurcating the country down the middle with Berlin in the center. Turns out, geography was not my strong suit. The city of Berlin sits several hundred kilometers to the east of the line that divided West Germany from East Germany.

Toward the end of the Second World War British and American troops attacked Germany from the west and the Soviets attacked from the east. The Soviets arrived in Berlin several days before Western forces, and the city was divided among the conquering powers by a special agreement afterward. What became known as East Berlin was occupied and controlled by the Soviet Union. West Berlin was the other half of the city controlled by British, American, and French forces respectively. Ostensibly all of these forces were cooperating under the Allied Command, but the Soviet Union quickly chose to go its own route, operating its half of the city, like the rest of East Germany, as they alone saw fit.

So, what resulted was essentially a little Western island plunked in the middle of a red sea.

3) Why was the Berlin Wall built?

After the dust from the war settled and East Germany began to implement the Socialist strategies of their occupiers, many citizens saw better economic opportunities outside the Soviet system, and crossed over the porous border into West Berlin without any problem. The defections gradually increased over the years so that by the time the wall was constructed in 1961 literally hundreds of thousands of people were fleeing the so-called worker’s paradise every year.

The Wall was the brainchild of Walter Ulbricht, the East German Communist party leader who saw it as a legitimate measure to prevent his citizens from leaving. Interestingly, author Frederick Taylor points out that the Kremlin only begrudgingly agreed to have the Wall built in the first place, fearing, more than anything, that such an unprecedented action would be viewed by leaders in the West as an act of aggression and lead to out-and-out war.

4) Berlin Wall Escape Attempts

Although the wall made it more difficult to escape to the West, it didn’t curtail escape attempts altogether. In the first few hours of the Wall’s construction, desperate Easterners, sensing that their opportunity for freedom might soon close, trampled through weak sections of the barbed wire fence in droves.

Odd geographic quirks provided opportunities as well, where buildings that straddled the border could serve as a way through the wall by entering on one side and exiting out the unguarded windows on the other. Many people tried swimming across a sparingly guarded canal too, where some were shot or died of hypothermia.

Once more permanent structures were put in place escapers opted to go underground, crossing the border through the vast sewer system that still connected the two halves of the city. Student groups often spearheaded these escape attempts, and were initially successful, but were eventually infiltrated by East German Stasi agents and compromised.

Taylor writes, “Such escapes were lucky or carefully planned, or both. Even before the Wall was fully fortified, to approach the border head-on and alone was perilous business. Between 13 August and 31 December 1961, according to Stasi figures, a total of 3,041 people were arrested as a result of failed escapes to the West.” (p. 296)

5) East German Soldier Jumping Over Barbed Wire

Easily one of the most iconic images associated with the Berlin Wall is that of Corporal Conrad Schumann, an East German border guard, jumping over a strand of barbed wire during the first few hours of the Wall’s construction, and thereby defecting to the West.

Taylor’s explanation of the event is fascinating, “All Schumann ever said, then or later, was that he hadn’t wanted to shoot anyone. Going West was a way of avoiding a moral dilemma…. Schumann was the first ‘deserter’ but by no means the last. During these first thirty-six hours, nine more border guards would flee to the West, jumping the wire, crawling under it, or in one case scaling a factory wall.” (p. 241)

The coda to the story, however, was something that I had never heard. After the Wall was torn down and the two Germanys reunited, Schumann returned to visit his old family and friends in the East. Sadly, after enduring decades of East German propaganda that painted Schumann as a defector, traitor, and an enemy of the State, his former associates wanted nothing to do with him. Tragically, Schumann took his own life not long after.

6) Ich Bin ein Berliner

The United States was none-too-pleased with the construction of the Wall, but, like the Soviets, was also treading softly to avoid another world war. President Kennedy arrived in 1963 to tour the city and raise morale of the besieged citizens.

So what’s up with Kennedy’s famous speech? The phrase “Ich Bin ein Berliner” and the accompanying video have been a staple of patriotic historical video montages for decades, but what does it actually mean? Why would Kennedy go around calling himself a citizen of Berlin?

Sadly, the answer to these questions has nothing to do with jelly donuts. A myth has circulated for many years about the grammatical structure of Kennedy’s statement in German. It says that because Berliner is also a colloquial German term used for a jelly donut, Kennedy was actually likening himself to a sweet morning pastry.

Linguists, however, have since debunked this idea. Kennedy relied on an expert translator and delivered the phrase correctly. Too bad, right?

What Kennedy was really getting at, was the idea that if free people are surrounded by a wall, then they are not really free. By calling himself a citizen of Berlin, Kennedy was saying he identified with Berlin’s desire for true freedom, and that anyone who doubted how bad the situation was there, should come and see for himself.

7) Line Painter Private Koch

Another story I hadn’t heard before was that of Private Hagen Koch, an East German soldier, whose job it was to survey and delineate exactly where the Wall was to be built. It was Private Koch who, in response to jeering protesters from the West, marched to the famous border crossing known as Checkpoint Charlie and painted a literal white line on the street. According to Taylor, “…ignoring yells and catcalls from the Western side, Koch straddled the border. Bending to his work, he painted a precise white line to show the ‘imperialists’ where East Berlin began.”

Koch’s coda is probably just as fascinating as Schumann’s. After a long military career, Koch got a job working for East Germany’s Department of Cultural Monuments. Probably most significant of his duties at this post was selling off the remaining intact sections of the Wall after it had been disassembled. Koch was literally right next to the Wall for both its initial construction and ultimate demise.

In the spring of 1990 he sold off the remaining 81 authentic Wall pieces at auction. These pieces now reside in museums, outdoor art exhibits, businesses, and homes. For some of the more surprising locations, you’ll want to check this out.

8) What Caused the Fall of the Berlin Wall?

This question demands a complex answer that Taylor presents well in the book, but I’m ill-equipped to explain in a blog post. Part of the answer has to do with the economic stress the East German government was experiencing. Their thimblerig strategies for moving money to cover debt was beginning to collapse. Internal protests were putting pressure on the government to change. Hungary disabled its border fence with Austria, allowing thousands of East Germans to suddenly flee the country relatively unimpeded.

The most simplistic answer though, and also one of the most compellingly dramatic moments in the Wall’s history, had to do with a simple misquote by an East German official during a press conference. By accidentally saying that effectively all travel restrictions would be lifted immediately he was inadvertently declaring that the Berlin Wall that held East Germans back from the West for more than three decades was suddenly moot.

Thousands of East Germans massed the border crossings. After tense hours of waiting, they broke through the barriers on their own. East Germany’s decision not to fire on the crowds of its own citizens allowed the Wall to come down peacefully.

Some Summary Thoughts

Why does the Berlin Wall matter? I think there are plenty of good reasons. First of all, divided countries still exist, as do contentious, heavily armed and barricaded national borders, like those between North and South Korea, Israel and Palestine, the United States and Mexico. The freedom to move between sovereign nations, and the rights of those nations to detain their own citizens are important questions to grapple with. In spite of the Wall, Germany was able to unite as one nation again, even after so many years apart. In an odd way, the demise and aftermath of the Berlin Wall can give us hope that similar things could happen other places as well.

If you are interested in learning more about the Berlin Wall, I highly recommend Frederick Taylor’s Book The Berlin Wall: A World Divided 1961-1989. It offers virtually anything you’d ever want to know on the topic.

Have your own thoughts on the Berlin Wall? Know some things not mentioned here? Have a correction or confirmation? Leave your comments below.

Also, if you liked this post click the +Follow button on the bottom right of your screen. Thanks!